In 1896, American architect Louis Sullivan, known as “the father of the skyscraper,” coined the phrase “form follows function,” which rapidly became the fundamental guiding principle for many architects. The essential idea is that the form or shape of a building—or indeed of any object or system—should be driven primarily by its intended function, that is, what the system does (its capability) and why (its purpose).

The fundamental importance of purpose has led many architects of enterprise systems to adopt the phrase “fitness for purpose” as the most basic requirement of their architectures. This has become so common that it seems “fitness” and “fitness for purpose” have become synonyms. This is unfortunate. Why? Because it obscures a second meaning of “fitness”—fitness for context— that has become increasingly important with the growing frequency and impact of disruptive contextual change.

For example, Sears and many other “brick-and-mortar” retailers were fit for purpose but not fit for the emerging Internet commerce context. They were disrupted by Amazon and other online retailers because shoppers wanted the convenience of ordering from their computers and mobile phones, and they also wanted to know about the experiences of previous buyers of products they were considering. While some brick-and-mortar retailers managed to adapt quickly enough, others failed to keep up with the new de facto standards for convenience, fast shipping, and product availability set by Internet commerce giants.

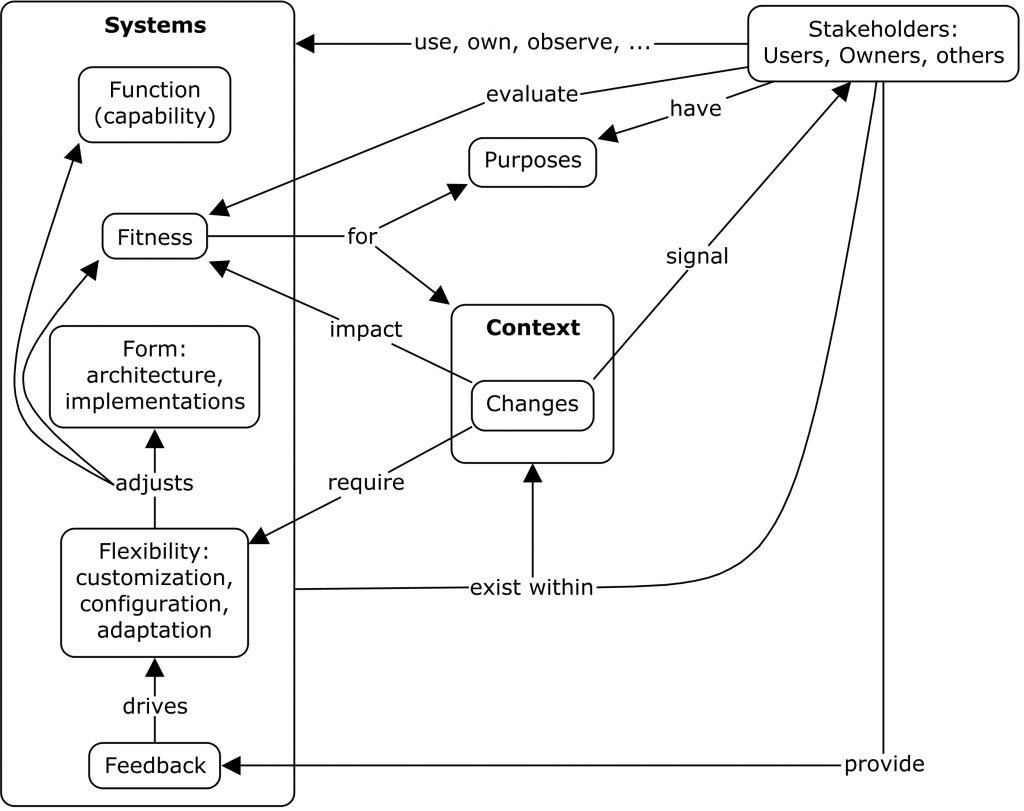

The following diagram shows how form, function, and fitness relate to each other and to two other concepts, flexibility and feedback.

Enterprises are essentially social systems, with people—stakeholders—at their core and indeed throughout their operational and business environments. Enterprises are complex, able to learn, and typically adapt well to changes in their context. And they nearly always aspire to be long lived—to survive and thrive—because that is in the stakeholders’ interests.

In other words, stakeholders care about “fitness for context.” In fact, it is the stakeholders’ evaluations of the enterprise’s changing fitness for context that cause them to provide feedback on the enterprise and its constituent systems. If the feedback is persuasive (e.g., obviously spot-on or expressed with strong feelings), it will drive enterprise decision makers to adapt their systems to improve their fitness.

Ideally, system architects and developers will have built considerable flexibility into their architectures and implementations (the systems’ “form”) so that they can be readily customized, configured, or adapted. How do architects know if the built-in flexibility is sufficient? They don’t. They make informed approximations from their experience and extrapolation of trends.

But the flexibility will not be enough to handle emerging issues that are beyond the architects’ experience and extrapolations. Architects must work with trend spotters and key stakeholders, especially strategists, to remain aware of potentially significant new contextual developments and investigate them quickly.

One good practice is to continuously monitor all stakeholder feedback and consider whether the systems have enough built-in flexibility to address new stakeholder concerns. If the flexibility is insufficient, new initiatives are needed to improve it.

If the context is relatively stable (its rate of disruptive change is low), fitness for context will likely not be top of mind in architectural decision making. But architects and stakeholders put their enterprise at risk if they ignore fitness for context completely. It is almost always better to keep an eye out for what may be coming and to find and fix weaknesses before they become liabilities. As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

We agree with Sullivan’s identification of function as the primary driver of a building, object, or system’s form. But what about the so-called “non-functional” requirements, like user experience, security, economy, responsiveness, etc.? These refer not to “what” the system does but “how.” When Sullivan came up with his “form follows function” principle, some building architects pushed back, asking what about aesthetics? Surely that must have a place in building architecture. Of course it does, just as do all of the so-called “non-functional” requirements. Isn’t this a problem for Sullivan’s dictum?

It might seem so, but the problem disappears when we realize that many of these “non-functionals” are crucial for the system to truly function as desired. We need to take a more complete view of the system’s purpose. For example, a bank building is not merely a place for conducting financial transactions. It is also an important factor in shaping its prospective customers’ feelings about whether the bank is a safe institution to hold their money. If the building leaves potential customers worrying about whether they should trust the bank, the building has failed to achieve its over-arching purpose. Similarly, a problematic user experience or privacy concerns can stop users from using an application or using it effectively.

Summing up, fitness for purpose is essential in architecting an enterprise and its constituent systems. But fitness for context is also crucial for enterprises to survive and thrive, especially in disruptive times. One of our favorite quotes that captures this Darwinian idea is engraved in the floor of the California Academy of Sciences headquarters: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”